Plastinates are a game changer in KansasCOM’s anatomy lab.

By Ian Morris

SUMMARY:

- KansasCOM’s multimodal approach to anatomy education includes using plastinated specimens.

- Plastinated specimens offer many benefits that make them easier than dissection to use, including that they don’t require special storage, they are easy to handle, and they last for many years.

- The students at KansasCOM are already finding plastinates a valuable addition to their education in osteopathic medicine.

The study of the anatomy of the human body is an essential part of medical instruction. For hundreds of years, the primary means of allowing students to view human structures was by using dissection of human body donors. These days, technological advances have provided more options, and, since its founding, KansasCOM has been at the forefront of employing technology in all phases of its osteopathic medicine curriculum, including anatomy education.

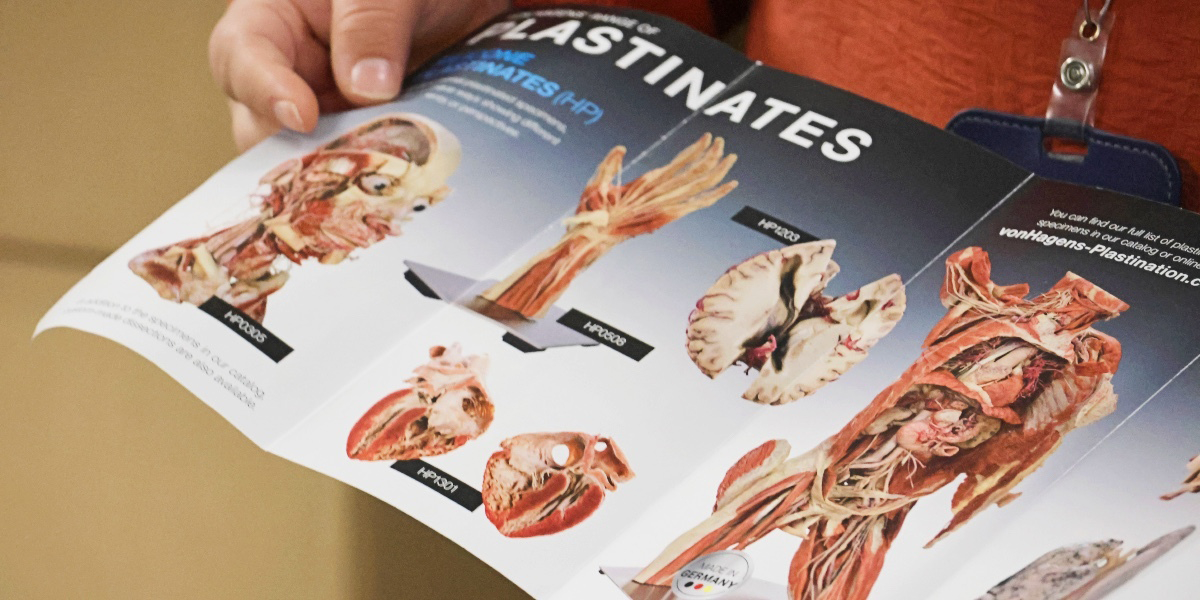

“We strive for a multimodal approach,” says Shannon Curran, director of the Anatomy Laboratory, who has been teaching anatomy for 10 years. Among the tools available in the lab are 3D holographic models; Sectra Tables that display cross-sectional anatomy “dissected” with touchscreens; and the newest addition, plastinated specimens. These are actual human specimens with plastic injected into their systems to replace water and fats.

Given their composition, plastinates are more versatile than conventional specimens. Here are five reasons why KansasCOM uses plastinated specimens for anatomy education.

1. Plastinated specimens are easier to maintain than wet human donors.

Plastinated specimens are dry and odorless—just two reasons why anatomists find them more convenient to work with.

Given that dissection is of wet human donors, extraordinary steps must be taken to prevent their decay. They require a wet lab, which includes refrigeration and special ventilation. Additionally, there are health regulations that must be followed to use them. Plastinated specimens, on the other hand, are dry and odorless and therefore can be used in a conventional indoor environment. The professionals who prepare the bodies for display preserve rather than destroy anatomical details. “That is their job,” Curran says. “We preserve so many details, and they’re beautiful and pristine dissections.”

Issues surrounding the availability, durability, and storage of wet human donors place demands upon medical colleges that wish to make them available to students for study. Thus, new technologies, including plastination and 3D imaging, are increasingly being used and improved.

2. Plastinated specimens are easier to store than wet human donors.

Plastinated specimens can be kept in cabinets just like other educational tools.

The ease of storing and maintaining plastinated specimens gives medical colleges and their instructors more flexibility in developing their collections. The specimens can be entire bodies or individual organs. KansasCOM has recently added to their original supply. “The students have had two sessions with donor hearts so far,” Curran says, “and I’ve been really impressed with how they have worked with the hearts and interacted with them.”

This also means they are portable, so that they can be used for instruction outside of a lab setting. For students of osteopathic medicine, a field in which hands-on examination is crucial, witnessing the structures of the body can be as important as actively dissecting a human donor.

3. Plastinated specimens last much longer than wet human donors do.

Each plastinated specimen is an investment in decades of laboratory use.

As wet human tissue, human body donors used in dissection last only about one year before they must be disposed of, regardless of the conditions in which they are kept. On the other hand, “plastinates have a lifespan of a minimum of 20 years,” Curran says.

The short life of a wet human body donor highlights the reality that while organ donation is common, human bodies have always been difficult to obtain. The criteria for donation (that the body should not be obese or emaciated, been recently operated on or have suffered from a communicable disease, and is acquired locally) limits the pool of candidates. Therefore, shortages are endemic.

4. Plastinates are reusable, unlike wet human donors.

Wet human donors are perishable and can be used for only a short time.

Typically, human body donors provide opportunities for medical students to practice operating upon a human body. This means that each operation, such as opening the chest cavity, can be performed only once. “You are destroying much of what you are trying to preserve,” Curran says. “The biggest advantage of plastinates to me is that, because they last so long, we are able to honor the gift of the donor for a much longer time period.”

The scarcity and fragility of human specimens inspire a solemn respect for these remains. “These are people who have given their bodies to science and education, and they have given a gift to us,” Curran says. “The students gain empathy and respect for those that they’re working with, which in the long run helps them become a better physician.”

5. Plastinated specimens give students a clearer view of the body’s structures than wet human donors do.

“Plastinated specimens are dissected by the highly skilled dissectors,” Curran says. “They are the most pristine dissection that you will get.”

The expertise with which dissectors imbue plastinated specimens allows students to observe the most intricate dissections and the most details in a dissection. In contrast, in a typical dissection lab where students are performing the dissections, many of a specimens’ details are easily lost. In addition to preparing specimens to maximize visibility of the key structures, some blood vessels are injected with red and blue latex to distinguish the arteries and veins. For example, the arteries of the brain are injected with red latex to highlight the cerebral arterial circle for superior visualization.

Curran sees the acquisition of the plastinated specimens they have so far and the efforts to obtain more of them as evidence of the support of the college’s leadership to provide the best learning experience for their students. “The dedication of our leadership and the dedication of our educators has been amazing,” she says. “We are leaders in medical education. We want to produce doctors who are leaders in medicine, and that is something that we are striving for and something that I think we are achieving.”